The Lack of Tech Excellence in Agile Development

There is a lot of talk about agile but unfortunately, most of the time organizations are not really agile, despite the fact they do for example Scrum and claim to be agile. This article will go over the issues I think we, as an industry, have with agile, what agile probably was meant to be and how to get to what it should be based on what the creators of the agile movement actually had in mind.

What Does Agile Mean

According to the Cambridge dictionary it is defined in the context of business as this:

able to deal with new situations or changes quickly and successfully

The origin of the word “agile” is the latin word “agili(s)” meaning “able to move”, from “agere”, meaning “to do”. So the linguistic root ties directly to the philosophy of the agile movement: Agile methods emphasize doing and acting (from agere) rather than over-planning or theorizing.

Agility means being able to react. Reaction requires awareness, and awareness depends on feedback. Without proper feedback, agility is impossible. So how do we build this awareness? How do we get the right feedback? This article explores those questions, but first, let’s look at what our industry originally meant by agile—and what it has become.

The Agile Manifesto

In 2001 a lot of well known and competent people like Kent Beck, Alistair Cockburn, Ward Cunningham, Martin Fowler and Robert C. Martin and more published the agile manifesto.

Manifesto for Agile Software Development

We are uncovering better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others do it. Through this work we have come to value:

Individuals and interactions over processes and tools Working software over comprehensive documentation Customer collaboration over contract negotiation Responding to change over following a plan

That is, while there is value in the items on the right, we value the items on the left more.

In the last few years some of the original signatories of the manifest expressed that they are unhappy with what agile has become, basically a thing that is sold as Scrum and SAFe, a certification industry to some extent. We’ll explore their point in-depth after the next section, the principles.

The Agile Principles

There are thirteen principles in total behind the agile manifesto. Here is the link to the original page.

- Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software.

- Welcome changing requirements, even late in development. Agile processes harness change for the customer’s competitive advantage.

- Deliver working software frequently, from a couple of weeks to a couple of months, with a preference to the shorter timescale.

- Business people and developers must work together daily throughout the project.

- Build projects around motivated individuals. Give them the environment and support they need, and trust them to get the job done.

- The most efficient and effective method of conveying information to and within a development team is face-to-face conversation.

- Working software is the primary measure of progress.

- Agile processes promote sustainable development.

- The sponsors, developers, and users should be able to maintain a constant pace indefinitely.

- Continuous attention to technical excellence and good design enhances agility.

- Simplicity–the art of maximizing the amount of work not done–is essential.

- The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams.

- At regular intervals, the team reflects on how to become more effective, then tunes and adjusts its behavior accordingly.

As you can see the original manifesto was small and short, the principles easy to read and understand. The principles already tell you what you need to do to become agile, they just don’t tell you the methodology, at least not directly. The principles are easy to read but tricky to interpret and implement. I’ll probably write another article just about them.

Let’s check two of them out and use them as examples.

Working software is the primary measure of progress.

What does “working” mean here? This is up to you, your business and your context. You can go by acceptance tests, Service Level Objectives that must be fulfilled, pick what helps you to define “working”.

Here is a more complicated one:

Build projects around motivated individuals. Give them the environment and support they need, and trust them to get the job done.

How do you figure out if people are motivated? What environment do they really need? Did you ask them or did you just assume? Again, the methodology is up to you. But let’s take something in advance: Just throwing Scrum or SAFe on this won’t make you agile.

Agile is Dead, long live Agile

Several original signatories of the Agile Manifesto have become vocal critics of how “Agile” has evolved in the software industry, expressing deep concerns about its transformation from a set of values and principles into a commercialized industry that contradicts the original intentions of the movement.

Ron Jeffries, one of the creators of Extreme Programming (XP) and a signatory of the Agile Manifesto, published a prominent 2018 article titled “Developers Should Abandon Agile.” His key criticisms include:

“When ‘Agile’ ideas are applied poorly, they often lead to more interference with developers, less time to do the work, higher pressure, and demands to ‘go faster’. This is bad for the developers, and, ultimately, bad for the enterprise as well, because doing ‘Agile’ poorly will result, more often than not, in far more defects and much slower progress than could be attained. Often, good developers leave such organizations, resulting in a less effective enterprise than prior to installing ‘Agile’.” - Source

Martin Fowler has been equally critical of what he terms the “Agile Industrial Complex.” In his 2018 keynote “The State of Agile Software in 2018,” he outlined three major challenges:

“Our challenge at the moment isn’t making agile a thing that people want to do, it’s dealing with what I call faux-agile: agile that’s just the name, but none of the practices and values in place.” - Source

Dave Thomas, co-author of “The Pragmatic Programmer” and another manifesto signatory, delivered a famous 2015 talk titled “Agile is Dead,” where he argued for retiring the word “agile”:

“The word ‘agile’ has been subverted to the point where it is effectively meaningless, and what passes for an agile community seems to be largely an arena for consultants and vendors to hawk services and products.” - Source

On Commercialization: Thomas explains how the transformation occurred: “Once the Manifesto became popular, the word agile became a magnet for anyone with points to espouse, hours to bill, or products to sell. It became a marketing term.”

Robert C. Martin has criticized how agile was hijacked by certification programs:

“[Agile] certification turned into this ‘siren song,’ and it attracted, frankly, all the wrong people. Agile was developed by technical people. It was a creation of the software industry – PROGRAMMERS sat in that room and created the Agile Manifesto and the agile principles. And then came certification. And with certification, hordes and hordes of project managers started to get certified.” - Source

Martin argues that “any attempt to employ Agile practices without the technical practices is doomed to fail” and laments the shift away from the technical excellence that was fundamental to the original vision. Source

Ward Cunningham, inventor of the Wiki, has expressed his philosophy that “I’d rather move on to the next idea than fight to keep the last one pure”, while Jim Highsmith continues to work on “Reimagining Agile” initiatives, suggesting ongoing dissatisfaction with the current state.

Kent Beck, the creator of Extreme Programming, has observed how agile was co-opted by existing power structures: Core Quote:

“Along came Agile and for a moment it looked like a threat. So the power structure co-opted it. And now it wasn’t a threat anymore. Now the people who are extracting more than their share of the value can still extract more than their share of the value.” Source

I highly recommend you to watch this video with Kent Beck.

Summarizing the Critique

The original manifesto signatories share several key criticisms:

- Commercialization Over Values: The transformation of agile from a set of values into a profitable industry

- Process Over People: The emphasis on following prescribed processes rather than empowering teams

- Certification Industrial Complex: The proliferation of meaningless certifications that miss the point

- Loss of Technical Excellence: The abandonment of engineering practices in favor of project management

- Imposition vs. Self-Organization: The contradiction of having agile methodologies imposed from above

- Faux Agile: Implementations that use agile terminology while violating agile principles

These criticisms collectively suggest that many of the original manifesto authors believe the agile movement has been fundamentally corrupted, turning into the very thing it was created to oppose: a rigid, process-heavy, commercially-driven approach that prioritizes compliance over collaboration and value delivery.

Technical Excellence: The Missing Piece

The lack of technical excellence is probably one of the reasons why so many agile transformations fail. Many of the original manifesto authors, like Kent Beck, Robert C. Martin, and Martin Fowler, consistently emphasized that technical excellence is not optional - it is foundational to sustainable agility. Without it, teams cannot safely adapt their processes or truly embrace self-organization.

Robert C. Martin has consistently emphasized that the manifesto didn’t adequately address technical practices. He believes that “clean code” and technical craftsmanship are essential for true agility. Many modern agile implementations focus on management practices while ignoring the engineering disciplines that make rapid, sustainable development possible.

What Does Technical Excellence Mean

Technical excellence goes beyond writing “good code” and focuses on building sustainable, long-term quality into software systems. It encompasses sound architecture and design that keep systems modular, extensible, and resilient, along with a culture of refactoring to reduce technical debt. Quality is baked into the delivery process through automation such as CI/CD, test automation, and infrastructure as code.

It also requires broad and deep testing practices, ensuring systems are reliable across functional, performance, and security dimensions. Collaboration practices like pair programming, code reviews, and shared ownership strengthen team knowledge and prevent silos, while observability and operational readiness make systems transparent and maintainable. In short, technical excellence is about designing and evolving software so it remains adaptable, reliable, and valuable over time.

Foundations for Lasting Agility

The original manifesto authors seemingly envisioned teams of skilled craftspeople who could adapt their methods intelligently. This requires:

- Technical Excellence Foundation: Teams must master core practices before attempting process innovation

- Continuous Learning Culture: Organizations must invest in ongoing skill development, not just initial training

- Coaching Support: Experienced technical coaches help teams build both skills and judgment

- Patient Progression: Building true technical competence takes time—rushing to autonomy without skills leads to chaos

The path from low-skilled teams to self-organizing excellence isn’t immediate autonomy - it’s systematic capability building that eventually enables the kind of informed process choice the manifesto authors originally envisioned.

How to enable autonomous Teams

The principle “teams choose their own way of working” (self-organization) only works if teams have the competence and discipline to do so. If they don’t yet, you risk chaos or cargo-cult agile.

Cargo-cult agile is the practice of adopting the rituals, ceremonies, and terminology of agile methodologies without understanding or embracing the underlying principles and values, leading to a lack of genuine agility.

- Guardrails instead of freedom

- Define non-negotiable items (e.g. coding standards, CI/CD, mandatory reviews).

- Allow freedom inside those boundaries.

- Over time, loosen constraints as maturity grows.

- Coaching and mentoring

- Agile coaches, tech leads, or pair programming to raise skill levels.

- Explicit training in practices like TDD, refactoring, CI.

- Incremental empowerment

- Start with prescribed practices (Scrum by the book, trunk-based development).

- As teams prove competence, let them adapt and evolve their process.

- Shared learning mechanisms

- Communities of practice, guilds, brown-bag sessions to spread tech excellence.

- Encourage cross-team alignment on best practices.

- Hiring and structure

- If skill levels are too low, sometimes the organization must invest in stronger engineers or create hybrid teams mixing senior and junior developers.

Lower-skilled teams shouldn’t have full freedom at first. They need scaffolding until they develop enough capability to truly benefit from autonomy. Autonomy is earned by demonstrating competence.

Here’s a simple, staged example model you can use - think of it like a maturity ladder for agile teams, balancing autonomy with competence. Take it as an example, it is by no means thought to be generalized. Figure out where you, as an organization are and what steps you think you need to evolve.

| Level 1 – Guided | Level 2 – Supported | Level 3 – Emerging | Level 4 – Self-Organizing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Low skill, little agile/tech practice | Basic agile understanding, starting with coaching | Consistent engineering practices (TDD, CI/CD, refactoring) | High technical excellence, strong agile mindset |

| Process | Follow prescribed framework strictly (e.g. Scrum by the book) | Prescribed, but small adaptations allowed | Teams experiment with process adaptations | Teams design their own way of working |

| Guardrails | Mandatory reviews, CI/CD, coding standards set centrally | Retros guided by coach/lead, central DevOps practices enforced | Quality metrics and standards monitored | Only org-wide constraints (e.g. security, compliance) |

| Autonomy | Very limited | Moderate - adapt rituals in safe boundaries | Increasing - freedom within outcome/quality criteria | Full - teams own process and practices |

Enabling Agility

There are, in my opinion, two primary prerequisites that enable agility:

- Working in small increments

- Feedback cycles

Small chunks are easier to process and also to change than big pieces of work. I think this is obvious and requires no further explanation. The key here is “change”. From a technical perspective I’m pretty sure that many developers know this problem: You get into a deep focus mode, start coding and end up with 1000 lines changed across 30 files, no tests, you’ll add them after your changes, maybe. This is the opposite of agility and working in small increments, this is causing a mess and waste of time.

The feedback cycles are required to provide, ideally, immediate feedback and to enable quality. If you haven’t already, you’ll have to invest into automating probably quite a few checks in your CI/CD pipeline. The whole purpose of your CI/CD pipeline is actually to serve as a feedback cycle. Don’t trust me? Ask Dave Farley or simply read his book “Continuous Delivery Pipelines”.

While I think that the ceremonies in Scrum could be useful - if they are done right - I also think that too few organizations focus on the technical aspects that enable agility.

Working in Small Increments

So instead of delivering a login, divide it into small pieces. Let’s assume that a proper login also contains a way to request a password reset. It will have some input validation and probably something else after a successful login.

- Start with the test. Write a test to check if the login page loads correctly.

- Make the test pass. Write the simplest code possible for the controller to return the page. Simple at this stage means just to return HTTP status 200!

- Commit. You have working code.

- Add a new test. Write a test to check that when you enter a username and password, you get a successful login.

- Make the test pass. Implement just enough code to handle the login and redirect.

- Commit. The core login now works.

- Add another test. Write a test for a failed login (e.g., wrong password).

- Make the test pass. Add the authentication check to handle a wrong password.

- Commit. The login is now more robust.

- …continue the cycle

Continue this process for every little part of the feature-input validation, password reset links, etc. Each step is a small, safe change that moves you forward without creating a huge mess. This is the opposite of a big, messy change that takes days and ends up with 1000 lines changed. Those small steps will also help your technical feedback cycles to run quickly, because you can execute a lot of them only against what you’ve changed.

You may have already noticed that this is basic Test-Driven Development: A test is a feedback cycle, that is one of the reasons to write it first. The other one is that the “driven” in TDD means that your test should also drive your design. But this is a subject for a whole different article.

Feedback Cycles

Imagine feedback cycles as instruments that help you drive safely: You don’t have to measure your fuel every few minutes, right? But I’m pretty sure you’ll want to pay close attention to the navigation, read road signs, and adjust your speed based on their information. You’ll also constantly measure the road in front of you to avoid collisions. These are feedback cycles, and you really should use them in software development as well.

They raise awareness and enable you to be agile if they are used and if they are used correctly. The shorter the loop (seconds → minutes → days), the faster you can adapt. Feedback cycles will make you aware of things going in the wrong direction.

Technical Feedback Cycles

- Unit tests – immediate feedback while coding.

- Linting / static analysis – instant feedback in the IDE or CI.

- Pair programming / mob programming – real-time peer feedback.

- Continuous integration build results – minutes after pushing code.

- Automated integration and end-to-end tests – minutes to hours.

- Feature toggles with canary releases – production feedback in minutes/hours.

- Monitoring and logging dashboards – near real-time runtime feedback.

Team-Level Feedback Cycles

- Code reviews / pull requests – peer feedback within hours.

- Daily stand-ups – alignment and blocking issues within 24h.

- Sprint reviews – stakeholder feedback every 1–4 weeks.

- Retrospectives – team process feedback every 1–4 weeks.

Your dailies should not be a reporting type of meeting where you describe what you did, but instead report what blocks you from getting your task done and who could help. A good meeting, if nobody is blocked, should not take more than the greetings and figuring out that nobody is blocked.

Regarding retrospectives, they are only useful if the artifacts produced by them lead to concrete actions. The job of the retrospective is to figure out what didn’t go so well and how it could be improved. Unfortunately I’ve seen it more often that nothing further happened after a retro. You’ve hopefully got the feedback, now take action and improve based on it! Remember that “agile” means “to do” things?

Customer / Business Feedback Cycles

- User story acceptance – product owner feedback within days.

- Usability testing / user interviews – direct user feedback weekly/monthly.

- A/B testing in production – live behavioral feedback in hours/days.

- Incremental releases – customer feedback in days/weeks.

I would like to put some emphasis on that developers should either watch recordings of user interviews, if that is possible, or even be directly involved in user interviews, to get first-hand experience about the impact their work has.

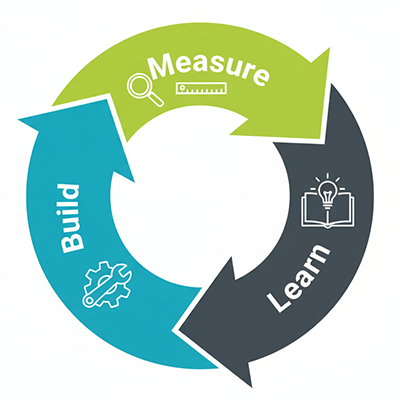

Feedback Cycles mapped onto Build-Measure-Learn

Mapped to the Build-Measure-Learn loop by Eric Ries, the author of “The Lean Startup”, the feedback cycles becomes arranged this way.

- Build → Code Quality Feedback

- Helps detect errors early while building software.

- Unit tests (seconds)

- Linting / static analysis in IDE (seconds)

- Pair / mob programming (real-time)

- Continuous integration build results (minutes)

- Automated integration / end-to-end tests (minutes–hours)

- Code reviews / pull requests (hours)

- Measure → System & Performance Feedback

- Validates whether the system works in context and performs as expected.

- Monitoring & logging dashboards (minutes–hours)

- Feature toggles & canary releases (minutes–hours)

- A/B testing in production (hours–days)

- Small incremental releases (days)

- Learn → Value & Process Feedback

- Checks if the right problem is solved and the team works effectively.

- User story acceptance (hours–days)

- Usability testing / user interviews (weekly–monthly)

- Daily stand-ups (24h feedback on team alignment)

- Sprint reviews (1–4 weeks, stakeholder value feedback)

- Retrospectives (1–4 weeks, process feedback)

If you are not familiar with the concept of Build-Measure-Learn, the idea is to build something small you can learn from, to gain insight and then to refine your product based on that. Eric Ries perspective is a product centric perspective, focused on learning about what to build next. The production of software is expensive, you want to make sure to build only what you need to make your next business decision on what to build. Again, you can see that this is also about breaking things down into small pieces and iterate over them.

“It is not necessarily the smallest product imaginable…it is simply the fastest way to get through the Build-Measure-Learn feedback loop with the minimum amount of effort.” - “The Lean Startup” by Eric Ries

As you can see here as well is that 2/3 of the process are still mostly of a technical nature, it is a lot about delivering quality early on and measuring, observing things. I think this further proves the point that agile is a lot about technical excellence and not just processes (e.g. Scrum).

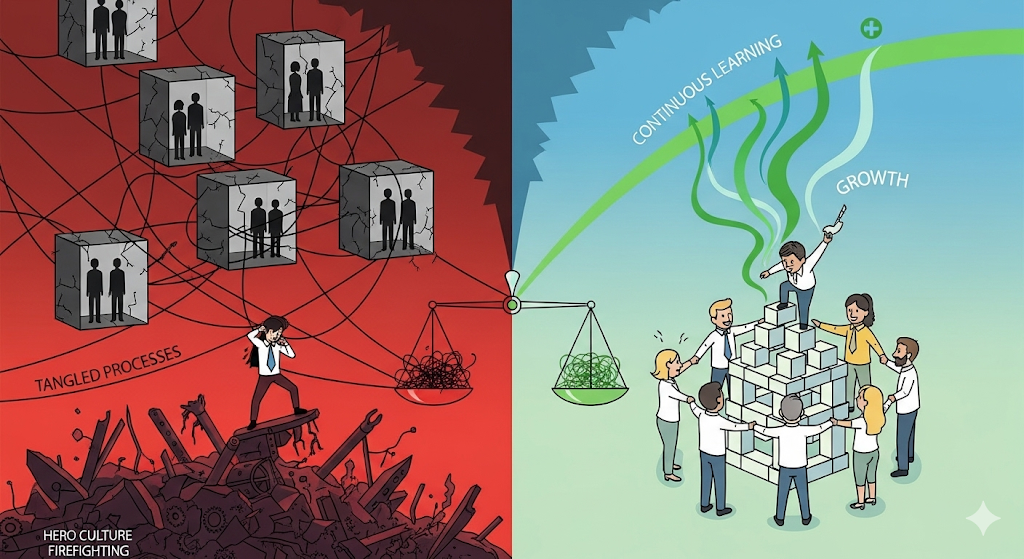

Organizational Culture

While agile processes and technical practices are critical, they cannot thrive in an environment that doesn’t foster and groom it. Organizational culture is the silent partner in any agile transformation, either supporting or sabotaging a team’s efforts. The right culture fosters the trust, psychological safety, and continuous learning necessary to achieve true agility.

An organization’s culture determines the long-term success of any agile initiative. Process without culture is merely a ritual. To truly become agile, a company must cultivate an environment where trust, learning, and psychological safety are seen as core business enablers, not just “soft skills.”

How Culture can support Technical Excellence

A culture that values continuous learning over being “right” encourages experimentation with new technologies and practices like Test-Driven Development and pair programming. When failure is seen as a learning opportunity rather than an offense, teams are more likely to take the necessary risks to improve their skills.

High-trust cultures empower teams to make their own decisions about how to best solve problems. Instead of micromanagement and command-and-control, leadership provides a clear vision and then trusts the team’s expertise. This autonomy is crucial for self-organization and allows teams to choose and refine their technical practices.

Teams need to feel safe to speak up without fear of negative consequences. When a developer can admit a mistake, point out a technical flaw, or challenge a bad design decision, the team can address issues early. This culture of psychological safety is essential for effective code reviews, retrospectives, and knowledge sharing.

A culture that prioritizes customer value above all else naturally encourages teams to seek out short feedback loops. This pushes them toward practices like frequent releases, A/B testing, and close collaboration with product owners, all of which are enabled by a strong technical foundation.

Many organizations are focused on output: the number of lines of code written, features delivered, or stories completed in a sprint. An outcome-driven culture shifts this focus to the impact of that work. The question changes from “Did we build it?” to “Did it solve the customer’s problem?”

How Culture can sabotage Technical Excellence

In a culture of blame, developers are less likely to admit to technical debt or propose difficult, long-term solutions. Instead, they’ll opt for quick, “hacked” fixes to avoid personal responsibility. This directly undermines the technical excellence needed for sustainable agility.

A culture that rewards “heroes” who pull all-nighters to fix broken systems discourages disciplined engineering practices. It values reactive firefighting over proactive prevention. Over time, this creates a dependency on a few individuals and builds up massive technical debt.

When teams or departments operate in silos, the free flow of information and expertise is blocked. An “us vs. them” mentality between development and operations (DevOps) or between teams prevents the holistic approach required for a modern, agile organization.

The probably worst one, because it is often driven by pressure from the business stakeholders, is a focus on immediate deadlines at the expense of quality leads to a disregard for practices like automated testing, refactoring, and code reviews. This “we’ll fix it later” mentality ensures that technical debt will compound, making future agility impossible or at least significantly harder to resolve. And that means increased cost and risks.

Conclusion

Unfortunately agile is nothing that you become quick and cheap.

Just by throwing a coat of “agile” management on bad or non existent best practice in the technical aspects of software development will certainly not make you agile. This is exactly processes over people instead of the original intention of people over processes.

On the other hand, you need to enable teams to become agile, that means you need to educate them, to teach them best practices. This will take time and is the inconvenient answer most managers won’t like to hear. A few weeks Scrum will fix it, right? Of course not.

My personal belief and experience is that agile is way too often seen as basically “just Scrum” by many people, missing the technical side of things, tech excellence. I have yet to meet a Scrum master who also teaches tech excellence and not just processes and ceremonies.

I’ve checked a few “agile coach” websites (no name calling here) and most of them do not even touch the subject of tech excellence but talk about organizational structures and management. To be honest: I wouldn’t hire those nor advise you to do so. Hire somebody with a holistic understanding of the tech side of things and management aspects. I actually found one person on Reddit who said he is an agile coach and he does trainings in the area of tech excellence as well. But he is, unfortunately, clearly the minority.

I also think that every organization can become agile, in the meaning of the original authors of the manifest, by carefully reading the principles and finding methods to apply them, or by finding a real agile coach that is not just adding processes but also helps to grow a culture that enables agile development.

For me personally, true agility is a combination of mindset, process, culture, and technical excellence.