The Limits of Human Cognitive Capacities in Programming and Their Impact on Code Readability

Programming is both a technical and cognitive task. While technical skills and knowledge are essential, cognitive abilities play a critical role in how effectively a developer can write, read, and understand code. Understanding the limits of human cognitive capacities can help software architects and developers design code that is more readable, maintainable, and less error-prone.

Complex vs Complicated

To be able to differentiate between complex and complicated code lets define what the difference actually is:

Complex refers to something with many interconnected parts, which may or may not be difficult to understand. A system can be complex but still function smoothly if its elements interact harmoniously. For example, the human body is complex, with various systems working together in intricate ways.

Complicated means something is difficult to understand or deal with due to its intricacy or convoluted nature. It often implies unnecessary difficulty or confusion. A tax form with unclear instructions might be described as complicated.

Therefore, cognitive complexity means the degree to which a piece of code or a system challenges the mental effort required to understand it, focusing on how the code’s structure, interdependencies, and flow affect comprehension, without necessarily being complicated or convoluted.

The Cognitive Load in Programming

Cognitive load refers to the mental effort required to process information. In programming, cognitive load is influenced by factors like code complexity, the number of concepts a developer must keep in mind, and how well these concepts are organized. Human cognitive capacity, particularly working memory, is finite, typically handling around 4 to 7 discrete items at a time. This limitation is crucial in programming, where maintaining a mental model of code structure, logic flow, and variables is necessary.

The Impact on the Developers

Complex code structures, such as deeply nested loops or convoluted logic, exceed the typical capacity of working memory. When developers cannot easily grasp the entirety of a code block, they are more prone to errors and misunderstandings. This underscores the importance of breaking down complex functions into smaller, manageable units.

- Naming Conventions: The cognitive load is also affected by how variables, functions, and classes are named. Poorly named entities increase the mental effort required to understand their purpose, making the code harder to follow. Adopting clear, descriptive names reduces unnecessary cognitive strain.

- Chunking and Modularity: Chunking is a cognitive strategy where individuals group information into larger, more manageable units. In programming, this is analogous to modular design—breaking down a system into discrete, self-contained modules. This approach aligns with the brain’s natural tendency to chunk information, making the code easier to understand and maintain.

- Consistent Patterns: Human brains are wired to recognize patterns. Consistent coding patterns and styles reduce the cognitive load because developers can predict how code is likely to behave. Inconsistent coding styles force developers to expend more cognitive resources to understand the deviations.

The impact on the Business

“Indeed, the ratio of time spent reading versus writing is well over 10 to 1. We are constantly reading old code as part of the effort to write new code. …[Therefore,] making it easy to read makes it easier to write.”

— Robert C. Martin, Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship

Because we not only write code for fun at work, being more efficient in understanding the code means also reduced costs for the business. If we consider that we read code 10 times more often than that we write code, it should be a natural conclusion that it is in the best interest of the business to reduce the time it takes to read and understand code.

Measuring Cognitive Load in Code

Measuring the cognitive load imposed by code is challenging but possible. Metrics like cyclomatic complexity (which measures the number of linearly independent paths through a program’s source code) provide a proxy for cognitive complexity. Tools like Halstead complexity measures also give insights into the mental effort required to read and understand code. These metrics can guide developers in refactoring code to be more comprehensible.

Metrics used in the Calculation to measure Cognitive Complexity

- Line Count - Measures the size of the method in terms of lines of code, which can indicate complexity and readability.

- Argument Count - High argument counts can suggest a method is doing too much or is overly dependent on external inputs, signaling a need for refactoring.

- Return Count - Multiple return points can complicate a method’s flow, making it harder to follow and maintain, often indicating a need for refactoring.

- Variable Count - A high variable count suggests a method is doing too much or is overly complex, helping ensure methods remain simple and focused.

- Property Call Count - Frequent property accesses may indicate high coupling to an object’s internal state, complicating testing and maintenance.

- If Nesting Level - Deeply nested if statements are harder to follow and may indicate a need for refactoring into smaller, manageable pieces.

- Else Count - A high else count can suggest complex or tightly coupled branching logic, making code more difficult to understand. If Count - A high if count can increase branching logic complexity, making the code harder to understand and maintain.

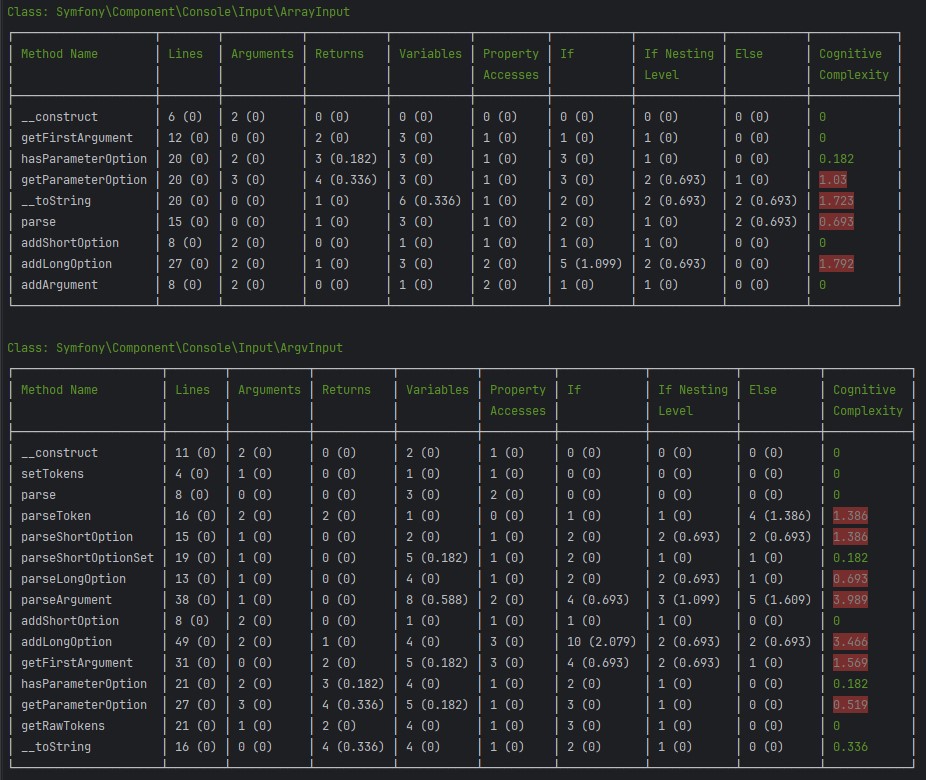

My Cognitive Code Analysis Tools

For PHP

Base on this I’ve written a cognitive code analyzer: Cognitive Code Analysis. It gathers these metrics and calculates a cognitive score from it.

You can install it via Composer by running:

1

composer require phauthentic/cognitive-code-analysis

For Java

Writing the same tool for Java, which I just started to get deeper into, is a fun task. It already works but I’ll continue to improve it until it matches the quality of the PHP tool, so consider it as work in progress and there is no build yet.

Score Calculation

A score is calculated that increases logarithmically as the input value exceeds a specified threshold. The result is 0 when the value is less than or equal to the threshold. When the value is greater than the threshold, the weight is calculated using a logarithmic function that controls the rate of increase.

Given a value of 75 that is greater than the threshold of 50, the function calculates the logarithmic weight as log(1 + (75 - 50) / 10, M_E) which results in approximately 2.302585.

Result Interpretation

Interpreting the results of any code metrics like cognitive complexity, cyclomatic complexity, efferent and afferent dependencies and other traditional measures requires understanding what each metric tells you about the code and how to use that information effectively. Each of those metrics are indicators but not absolute truths.

There are cases in which the code simply ends up with a lot of things that might result in a bad score but are necessary and acceptable under certain circumstances. For example a complex calculation or a complex algorithm might have plenty of variables and input arguments. If the problem can’t be divided (if it can you really should!) into smaller logical units (methods), the score for that method will inevitably be high.

- Bias - When it comes to cognition, consider that something that you perceive as easy or understandable, might not be the same for someone else. Especially if you wrote the code.

- Constructors - Constructors are often more complex than other methods because they have to initialize the object’s state. This can lead to higher cognitive complexity scores, which may be acceptable in some cases.

- Data Structure Building - Methods that build complex data structures or perform complex calculations that involve a large number of (input) variables, may have higher cognitive complexity scores. Typical examples here are methods like

fromArray()ortoArray(), mapping functions, that map between entities or JSON and XML generating code. This is often unavoidable and may be acceptable if the complexity is necessary for the task at hand. In this case it is recommended to ignore those methods. My tool provides a configuration for that.

Examples

Wordpress WP_Debug_Data

Class: \WP_Debug_Data

┌───────────────────┬──────────────┬─────────────┬───────────┬─────────────┬─────────────────────┬────────────┬──────────────────┬────────────┬──────────────────────┐

│ Method Name │ # Lines │ # Arguments │ # Returns │ # Variables │ # Property Accesses │ # If │ If Nesting Level │ # Else │ Cognitive Complexity │

├───────────────────┼──────────────┼─────────────┼───────────┼─────────────┼─────────────────────┼────────────┼──────────────────┼────────────┼──────────────────────┤

│ check_for_updates │ 5 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 │

│ debug_data │ 1261 (6.399) │ 0 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 105 (3.073) │ 20 (1.03) │ 58 (4.025) │ 3 (1.099) │ 33 (3.497) │ 19.122 │

│ get_wp_constants │ 143 (3.75) │ 0 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 9 (0.875) │ 0 (0) │ 5 (1.099) │ 1 (0) │ 5 (1.609) │ 7.333 │

│ get_wp_filesystem │ 59 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 9 (0.875) │ 0 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0.875 │

│ get_mysql_var │ 14 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 2 (0) │ 2 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 │

│ format │ 59 (0) │ 2 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 11 (1.03) │ 0 (0) │ 5 (1.099) │ 1 (0) │ 5 (1.609) │ 3.738 │

│ get_database_size │ 13 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 4 (0.336) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0.336 │

│ get_sizes │ 124 (3.497) │ 0 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 14 (1.224) │ 0 (0) │ 9 (1.946) │ 2 (0.693) │ 5 (1.609) │ 8.969 │

└───────────────────┴──────────────┴─────────────┴───────────┴─────────────┴─────────────────────┴────────────┴──────────────────┴────────────┴──────────────────────┘

Doctrine Paginator

Class: Doctrine\ORM\Tools\Pagination\Paginator

┌───────────────────────────────────────────┬─────────┬─────────────┬───────────┬─────────────┬─────────────────────┬───────┬──────────────────┬───────────┬──────────────────────┐

│ Method Name │ # Lines │ # Arguments │ # Returns │ # Variables │ # Property Accesses │ # If │ If Nesting Level │ # Else │ Cognitive Complexity │

├───────────────────────────────────────────┼─────────┼─────────────┼───────────┼─────────────┼─────────────────────┼───────┼──────────────────┼───────────┼──────────────────────┤

│ __construct │ 10 (0) │ 2 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 │

│ getQuery │ 4 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 │

│ getFetchJoinCollection │ 4 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 │

│ getUseOutputWalkers │ 4 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 │

│ setUseOutputWalkers │ 6 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 │

│ count │ 12 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 │

│ getIterator │ 46 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 2 (0) │ 9 (0.875) │ 2 (0) │ 3 (0) │ 2 (0.693) │ 2 (0.693) │ 2.262 │

│ cloneQuery │ 13 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 3 (0.182) │ 0 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0.182 │

│ useOutputWalker │ 8 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 2 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 │

│ appendTreeWalker │ 11 (0) │ 2 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 │

│ getCountQuery │ 25 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 4 (0.336) │ 1 (0) │ 2 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 0.336 │

│ unbindUnusedQueryParams │ 17 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 6 (0.588) │ 0 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0.588 │

│ convertWhereInIdentifiersToDatabaseValues │ 11 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 1 (0) │ 5 (0.47) │ 1 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0 (0) │ 0.47 │

└───────────────────────────────────────────┴─────────┴─────────────┴───────────┴─────────────┴─────────────────────┴───────┴──────────────────┴───────────┴──────────────────────┘

Conclusion

The limits of human cognitive capacities are a significant consideration in programming, impacting code readability and understandability. By acknowledging these limits and employing strategies to mitigate cognitive load, developers can produce code that is not only easier to work with but also more robust and less prone to errors. Measuring cognitive load through complexity metrics and utilizing cognitive science principles can lead to better software design and ultimately, more efficient development processes.

Papers & Studies

If you are interested, these pages and papers provide more information on cognitive limitations and readability and the impact on the business.

- Cognitive Complexity Wikipedia

- Cognitive Complexity and Its Effect on the Code by Emanuel Trandafir.

- Human Cognitive Limitations. Broad, Consistent, Clinical Application of Physiological Principles Will Require Decision Support by Alan H. Morris.

- The Magical Number 4 in Short-Term Memory: A Reconsideration of Mental Storage Capacity by Nelson Cowan

- Neural substrates of cognitive capacity limitations by Timothy J. Buschman,a,1 Markus Siegel,a,b Jefferson E. Roy,a and Earl K. Millera.

- Code Readability Testing, an Empirical Study by Todd Sedano.